SE: Sun & Fun

Back in my family home, we were sometimes visited by my grandmother’s brother, Andrzej Wiktor, a malacologist. The stories he told seemed as unreal as the ones in the novels of Jules Verne. He traveled to Papua New Guinea, interacted with the locals, became familiar with a different culture, climate and customs. He went there to study mollusks. Each newly discovered species had to be exhaustively described: its stages of development, functioning, how it reproduces, what it feeds on, where it lives and how it rests. The study is intensive and time-consuming. It requires patience and incisiveness. The result is presented in the form of drawings.

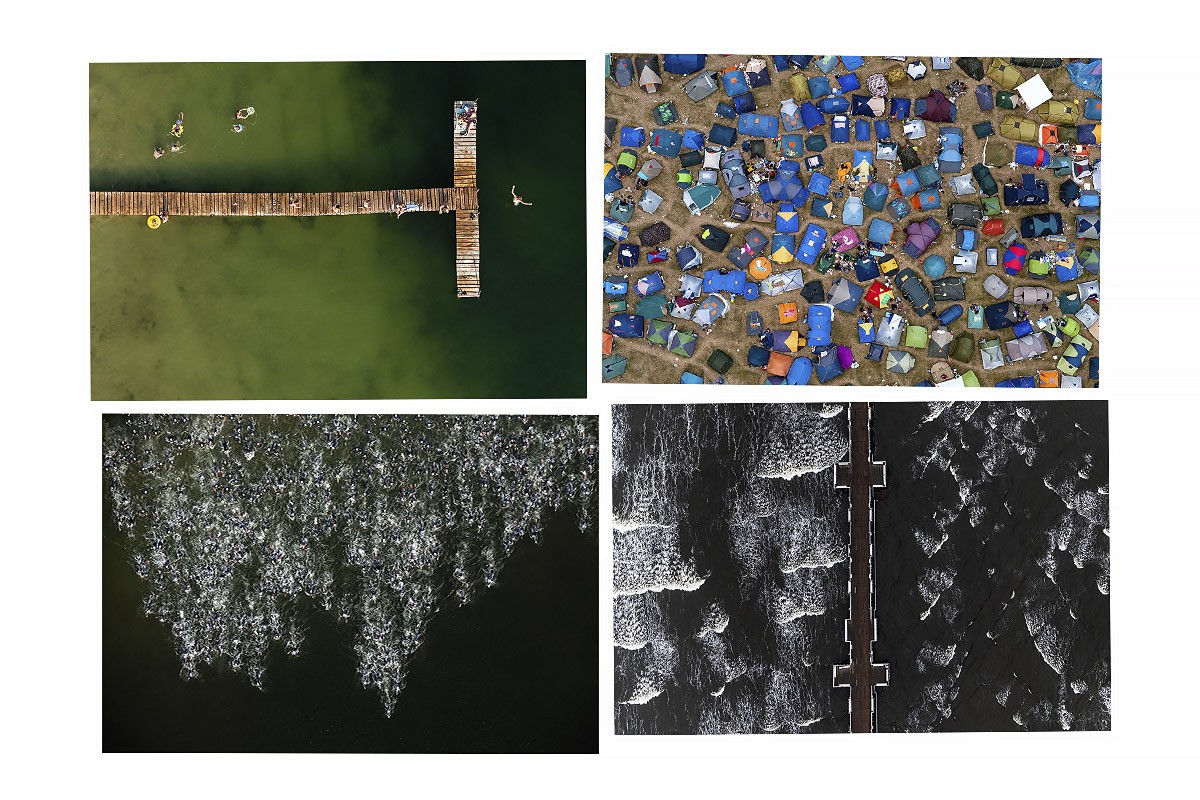

My work sometimes resembles that of a biologist: I study the human species. Each photograph presents some aspect of our presence on Earth. I don’t go to the end of the world to take them. The paraglider takes me far enough. I take off, reach the altitude of 150 meters and I begin my observation. I want to know how the people in my neighborhood pass their time outside: swimming, playing games, just being lazy. I peek in to see what’s inside their little fortresses set up on the beach.

With the first rays of sun, the sunbathing village on the beach awakens to its one-day life. It changes daily, but functions under strict rules. It’s got it all: main street paved with sand, narrow passages, tiny plazas and a tower with a view. There are fancy multigenerational residences and modest individual plots carved out from the common space. Ice-cream and beer trade is blooming. There was a volleyball court here just a moment ago, but it’s been claimed by the sprawling village. The number of beach wind screens grows as new residents arrive. Social life flourishes; everything is part of a fashion show. Even high above, I catch the ubiquitous scent of tanning oil. The village is transitory. Its short life is dictated by the movement of the sun: it grows during the day and dies down at sunset. Few remaining residents gather around bonfires at night; in the morning, the village rises like a phoenix from the ashes.

This is my account of a situation that took place on the beach in Władysławowo in July 2007. It accompanied a photograph I submitted to a contest. I decided to return to the beach the following year so that everyone could see what goes on in this extraordinary place. That’s how “A day at the beach” series began. Captions to the next series are extremely short: Władysławowo, 6 AM, 7 AM, 9 AM etc.

Never mind that flying to the beach at 6 AM meant waking up half the town. I didn’t care that it was Sunday. For years I felt I was on a mission and therefore had my privileges. If I didn’t go, the world would never discover what I had discovered. After the photo shoot I returned to my studio, described my photographs and sent them to the agency. In the afternoon the photos appeared online, together with the triathlon results. Things are different nowadays. Everybody knows what a triathlon looks like from above. Just like any other image, this one has been replicated a thousand times. The coverage is streamed live by a drone operator. I no longer wake people up on Sundays; I can sleep in myself.

Up in the air, I tend to focus on new phenomena of which nobody is yet aware. But sometimes I return to the beach, as it fascinates me more than any other place. You can read about it HERE.

Series presenting „One day at the beach” feature, won second prize in the Arts and Entertainment category of World Press Photo 2009.

The Sun and Fun series was - as part of the Side Effects project - awarded the World Press Photo 2015 second prize in the long-term projects category, and was included in the photo book „Side Effects” published in early 2014.