SE: Toxic Beauty

Heavy industry is a taboo subject. On one hand, there are “no entry” and “no photography” signs, barb-wire fences and security guards. On the other, local communities protesting against noise, odour and pollution. When I’m on a motorized paraglider, fences are no barrier for me. I fly over them to see what lies inside the walled-off space.

On a first such flight I thought about the motor. What if it stalls? Parking lots and lawns which could serve as emergency landing strips where entwined with wire and bristling with masts. Between them was an opening with a working fan the size of a truck. An impressive chimney towered above the grounds. A huge tank filled with some unnaturally colored and gelatinous substance sprawled on one side. The other one consisted of trees, electrified railroad tracks and a high fence. All this was being supervised by watchful security, reluctant towards any intruders, let alone daredevils entering from the sky.

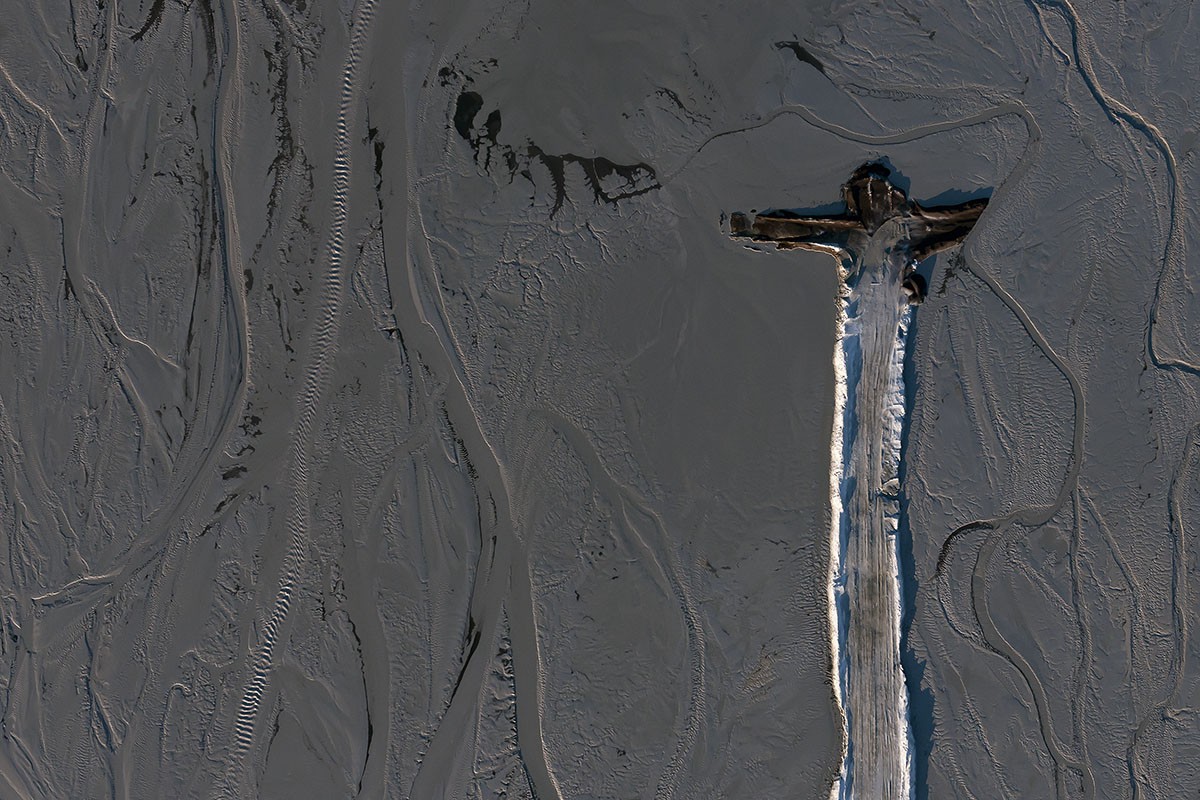

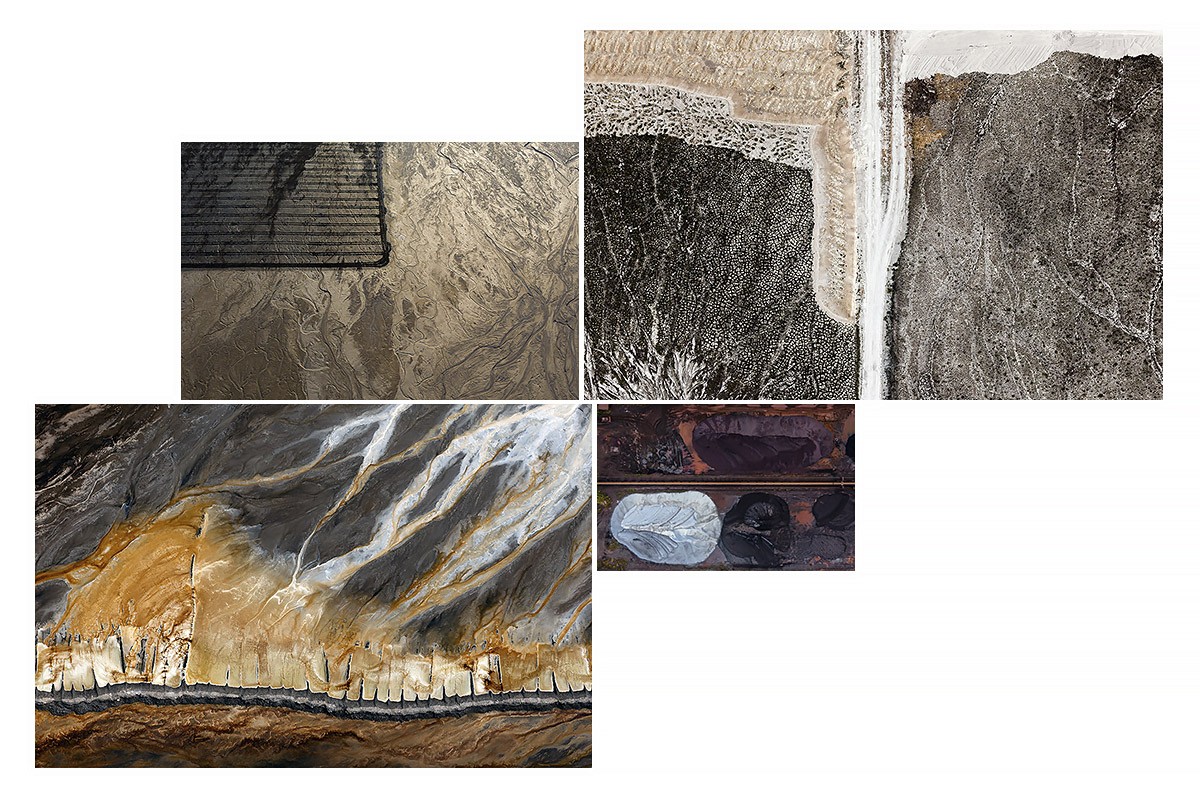

I gained altitude, listening to the rhythm of the engine. Was it working properly? Or did factory fumes alter the fuel-burning process? I made sure I was flying winward. I hovered over a tank with one km in diameter, filled with turquoise liquid and a grey mass. Some cesspool. Should I turn back? In front of me stretched a lunar landscape with infrastructure resembling a Soviet sci-fi movie, leading into a huge pit. Curiosity prevailed. I flew towards the bottom, sinking several hundred meters below the horizon, in the direction of machines the size of oil tankers. They were mining lignite. So this is where it’s extracted. I watched huge rotating shovels loading it onto a conveyor belt. Soon I was flying over the belts transporting raw material into the heart of the power plant. I felt its pulsating energy through my skin. The turquoise liquid and grey matter turned out to be ashes, a by-product of burning lignite. Such was the backdrop of the first photograph in the series, taken in the spring of 2007 and initially called “Prohibited Beauty”.

I started thinking about the nature of the place. Ashes from a barbecue are not much different from those generated by a power plant. What differs is the scale. The Bełchatów Power Plant burns a ton of lignite a second, emitting 100 000 tons of carbon dioxide a day, an equivalent of 6,5 million cars. Half of Poland relies on electric energy generated in this manner.

How can something toxic and stinking awaken my sense of beauty? Why does delight in a composition resembling a gingko leaf come before I realize what it is I am looking at? I started collecting photographs of such places. Each flight is an adventure and a risk, a delight and a fright. Chemical plants, open-pit mines, electrical power and heating plants, steel mills and coke plants as well as sulphur mines are spaces completely transformed to satisfy the needs of a modern society. Do we have the right to such interventions? Where is the line we shouldn’t cross? Toxic waste is often stored outside, becoming a burden to locals who pay a high price so that we can have paper, salt and a place to store our trash. Protesting isn’t easy when a polluting plant is the only employer in the neighborhood; changing regulations is difficult when the plant is a substantial tax payer.

I am happy to see my photographs accompanying debates on the costs of our civilization. Sometimes they serve one side of the argument, sometimes the other. That’s the way they are.

When during a flight I spot some industrial infrastructure, I am drawn to it like a moth to the flame. Possibly because I grew up in a new district of prefabricated blocks of flats, where we played hide-and-seek with construction workers. I am nostalgic for the old pranks and as curious as I was back then. Someday my motor will stall and I will land on some plant grounds. A surprised guard won’t know what to do with me, just as we humans don’t really know what to do with the knowledge of the costs our civilization incurs.

The Toxic Beauty series, presenting spaces affected by heavy industry, won second prize in the nature category of World Press Photo 2014. As part of the larger Side Effects project, it was again awarded second prize in the long-term projects category of World Press Photo 2015.